Effective and Ineffective Social Media Messages: When Backchannels Backfire

In this session of the social media class, we talked about how things can go wrong in social media networks, and, more generally, while communicating in a globally networked society. First however, we discussed how messages become viral in the first place. We learned about the SUCCES framework as a set of principles for making people remember a message, and then looked at examples where messages are highly memorable, yet ineffective: Even if people remember your message, it may not have the intended effect, and sometimes you achieve the opposite of what you were going for.

How Messages Become Viral

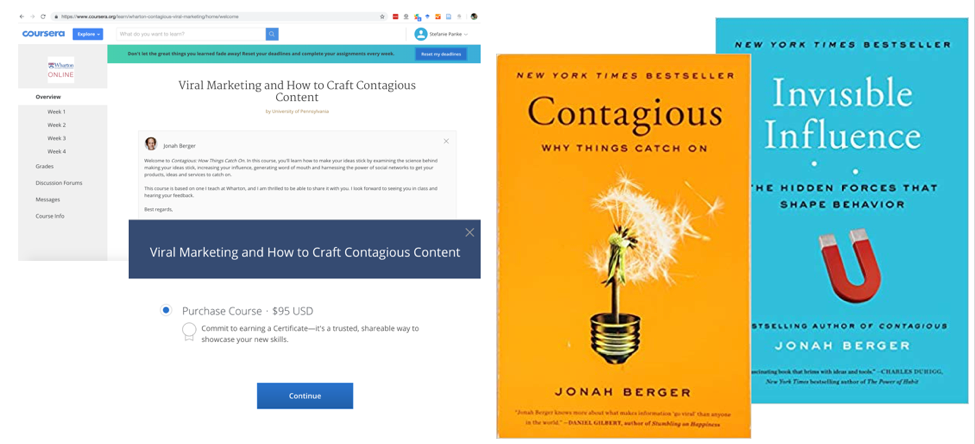

If you want to learn principles of effective social media marketing, the MOOC ‘Viral Marketing and How to Craft Contagious Content’ by Jonah Berger offers an amazingly well structured, accessible introduction that uses simple language and contains many concrete examples – an ideal resource for non-native English speakers, produced by a marketing professor who has authored two bestsellers.

The starting point of Berger’s MOOC is the observation that social influence, the effect of our social environment on our behavior and decision making, is what makes social media such a powerful tool.

“Looking at others for information is a key thing we do often. It’s a shortcut to judgment. It saves us time and effort to look to others in what they have done previously. […] This inference is much stronger when people have less time or motivation. If we don’t have a lot of time to make the decision and we’re not very motivated, we’re much more likely to turn to other’s to help us make that decision”. (Berger, Coursera, 2018)

In his lecture, Berger cited a study by the researcher Nicholas Christakis on how obesity can spread through social networks. The idea that a friend’s friends’ friends, or a spouse’s siblings’ friends, could have an influence on a person’s weight seems really creepy. However, understanding how social influence works offers an opportunity to reflect upon it, and consciously work against it by spending extra mental effort when the decision is important. I recently went through CPR training, and one of the first things you learn is to shake off the instinct to do what everybody else does (which typically is nothing). You first have to know that you typically look at others to model your behavior, and take cues from them to respond to a situation, because this awareness will – hopefully – allow you to apply your training and act decisively in an emergency.

Social networks offer many shortcuts to judgement based on the information behavior of others. As we saw in the last session on fake news, ideas can spread, whether they are true or not. But why do some ideas become popular while others fail? The SUCES framework from the book ‘Made to Stick’ by Chip and Dan Heath is a marketing framework for analyzing why some ideas stick. At the same time, it’s a recipe for crafting messages and memes that are memorable and thereby more likely to spread in social media (or ‘go viral’). The six principles are: Simple, Unexpected, Concrete, Credible, Emotional, Stories.

We specifically looked at the ‘unexpected’ principle. In his lecture, Berger sees three ways of achieving this principle: Doing something novel, breaking a pattern, and, lastly, but most importantly, creating a curiosity gap.

“To make something really sticky, to make something stick in memory, we need to hold their attention by opening up what’s called a curiosity gap. And what a curiosity gap is, is a mystery where people want to know the answer. It’s a little bit of information that encourages them to lean forward to find out more”.(Berger, Coursera, 2018).

Viral or Notorious? The Example of ‘Hornbach’

A recent advertisement campaign that exemplifies the idea of a curiosity gap is ‘the smell of spring’ campaign by the Germans hardware chain Hornbach. The campaign prompted significant backlash. The advertisement showed an Asian woman getting aroused after smelling dirty clothes worn by white men. “Deutsche Welle”, Germany’s international broadcaster, summarized the feedback “Racist, Sexist, Disgusting”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wAlyYXRtWvQ

What do you do when backchannels backfire? And why does this happen so often? While unexpected, simple, concrete, credible, emotional stories might stick in your memory really well, they can also oversimplify and offend. In this case, the company stressed that they did not view their message as racist, but merely as a commentary on the urbanized lifestyle.

In analyzing this spot and the surrounding debate, we tried to understand why campaigns want to say one thing, but indeed say a very different thing to large audiences. Can you be racist unintentionally, and was this the case for the Hornbach ad? The short answer is ‘Yes’. The likelihood of sending the wrong message in a diverse society is high – if you do not take the time and opportunity to leverage your networks to reflect upon your own background and implicit bias. Prior to the class, I had collected various blog posts with examples of discrimination and sexism that Asian women face, i.e., ‘yellow fever’, and reading through these stereotypes and how painful and unfair they are to everyday people made the reaction to the Hornbach ad predictable instead of surprising.

Critical Pedagogy and Gender in Social Media

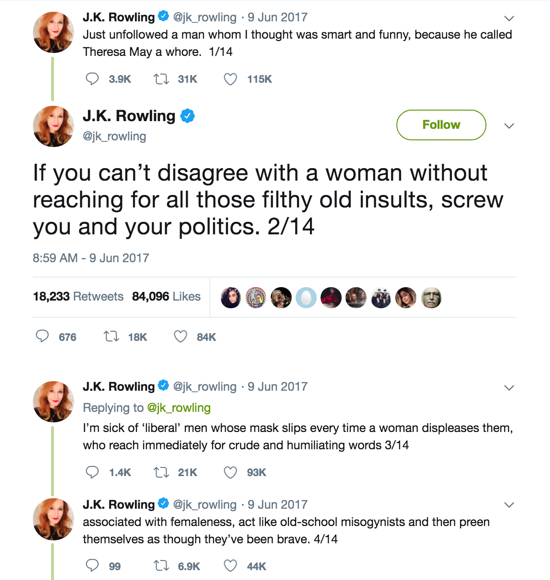

We used this as an opportunity to delve into ‘Critical Digital Pedagogy’. I shared one of my favorite quotes from a critical digital scholar: “No classroom is floating above the world in an imaginary context. Power, privilege and difference are a global currency and universal phenomena” (Chayla Haynes , 2018, Elon Conference of Teaching and Learning). In the same way, no social media message floats on the Web, and bounces around merrily in social networks without carrying the context and history of social class, gender and race, to name a few. In the webinar, I used J.K. Rowling’s tweet to specifically raise awareness how women are particularly vulnerable on social media – and I shared some stories of self-censoring, particularly on Twitter, to avoid visibility.

How can we design our social media messages so that they support learning, sharing, memory and, at the same time disrupt the codification of race and complicate gender, national origin, language, religion and geography? We talked about the importance of intergroup empathy and strategies for fostering it. Developing empathy allows us to understand and feel with others, and overcome prejudices and stereotypes. Ideally, every communication breakdown is a growth opportunity for society, groups and individuals to become more open and inclusive, to be kind rather than rude, and to make an effort to understand where the other person is coming from.

What else can go wrong? Adverse Effects of Campaigns

At the end of the webinar, we returned to Berger’s MOOC videos to highlight yet another way for social media messages to fail epically: Adverse effects based on social influence. An example is the ‘Just Say No’ anti-drug campaign from the 1980s. The ads presented various settings in which kids might be tempted to try drugs, and emphasized the correct response as ‘just say no’. However, children who saw the anti-drug ads, were not less likely to take drugs, they were more likely to use drugs.

“While telling people not to use drugs, the ads were simultaneously saying, other people are doing it. And whenever we tell people that other people are doing something, they’re going to be more likely to do it themselves”. (Berger, Coursera, 2018).

Berger cited a campaign intended in preventing people from taking souvenirs from a petrified forest national park as another example. One campaign stated ‘many park visitors have removed petrified wood from the Park, changing the natural state of the forest‘. Without the message, about 3% of people took petrified wood, with the message, the number tripled to 9%.

Bottom line, if we want people not to do something, we shouldn’t tell them that other people are doing it. I found this really fascinating, because a lot of our communication about environmental impact is structured like this: “Since many, many people are consuming single-use plastic every day, 8 million metric tons of plastics enter our oceans every year”. If we take the risks of adverse effects seriously, we need to rethink our communication strategies, and find ways to say “Many people are no longer using single-use plastic. Be one of them and protect the oceans”.

Overall, this was a difficult session to teach, because communication failures and unintended consequences happen to all of us, in both personal and professional contexts. It is much easier to talk about successes than failures, but mistakes happen all the time. The important thing is to learn from them. Many of us do :-).

Laura Tabor

May 1, 2019 at 11:08 am

Thank you for such an interesting article and perspective. I had not hear of the Hornbach video and found that a real eye opener. So many takes on it-all valid.