New Report: Seven Myths of AI Use – A Critical Perspective on Generative AI

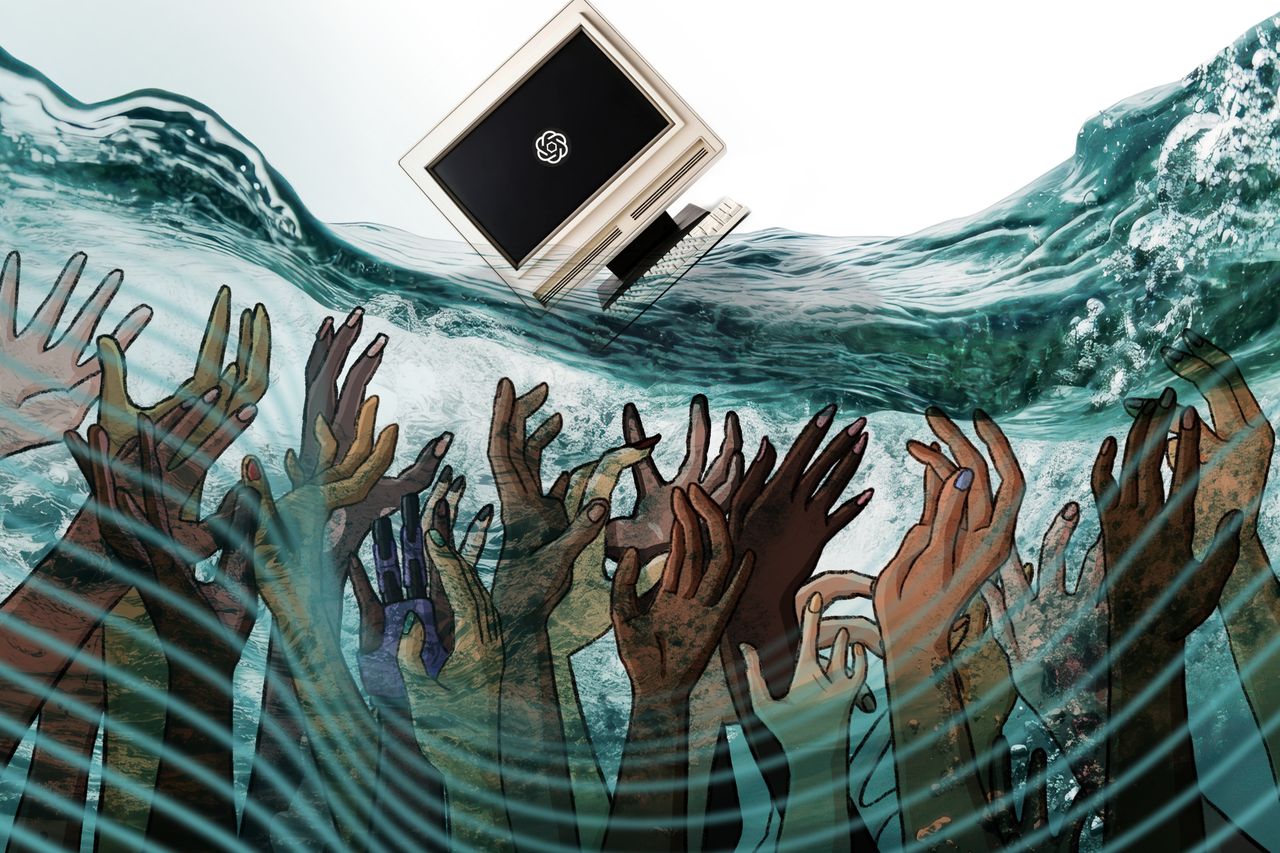

Rose Willis & Kathryn Conrad / A Rising Tide Lifts All Bots / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

These days, people can hardly use the Internet without running into generative AI—yet many everyday beliefs about “how AI works” are inaccurate in ways that matter especially for education, argues the position paper “Seven Myths of AI Use”. It was published by a team of six Austrian researchers: Sandra Schön, Benedikt Brünner, and Martin Ebner from Graz University of Technology (TU Graz), Sarah Diesenreither and Georg Krammer from Johannes Kepler University Linz, and Barbara Hanfstingl from University of Klagenfurt. At a time when we start to contemplate futures of “a country of geniuses in a datacenter” (Dario Amodei), this report summarizes some of the most prominent concerns towards generative AI.

Report Summary

Schön and colleagues argue that many of today’s problems with generative AI tools stem from widespread misconceptions about how these systems work—and how people interpret their outputs. They frame seven “myths” as working hypotheses that deserve heightened attention, and they explicitly position the paper as an awareness-raising piece meant to stimulate further research and debate.

Myth 1: AI tools are neutral, objective, and unbiased.

Because AI tools are “just computers” processing data algorithmically, their results are assumed to be neutral—uninfluenced by stereotypes or preconceptions. The authors argue AI outputs can reproduce injustices and prejudice from training data, are shaped by “system prompts” and other settings, are often not explainable, can vary for the same prompt, and can be deliberately influenced (e.g., via optimization or prompt injection).

Myth 2: AI tools function logically.

Since computers compute, it seems reasonable to assume AI tools also “do calculations” and follow logical deduction. The authors state that AI tools cannot calculate in the mathematical sense unless explicitly routed to an external computing tool, can be error-prone on logic problems, and (contrary to many users’ expectations) do not necessarily search the web for correct or up-to-date answers.

At first glance, this claim directly runs counter to the impressive capabilities of for example OpenAI Codex, Anthropic Claude Code, or even highly detailed fact-checking (Deep Background, see the interview with Mike Caulfield). However, the argument is more nuanced: The “myth” here is less “AI tools can’t do logic” and more: don’t assume logical deduction and computational properties of the model’s text generation—they’re often properties of the surrounding system (tool use, retrieval, verification).

Myth 3: AI tools think and learn like humans.

Because the AI discourse uses human/biological terms like thinking, intelligence, training, learning, and hallucinations, it invites the assumption that AI functions like people (or brains) do. The authors stress key differences: AI does not have human-like intelligence or learning (including emotions and lived experience), does not “think” through processes the way humans do, and lacks the kind of feedback loops that shape human learning.

Similarly, Stephen Downes recently stated: “I have what AI will never have: my own opinions and experiences (sure, the AI may eventually have it’s own opinions and experiences, but it can never duplicate mine). Now it is a bit of presumption on my part to suppose my opinions and experiences are worth sharing, but that’s a different issue”.

Myth 4: AI tools are empathetic.

If an AI tool’s output comforts, confirms, or emotionally moves us, it can feel as if the tool “understands” us—so people may assume the tool itself feels emotions and is empathetic. The paper argues that while AI can evoke strong emotions in humans, this does not mean the tool feels emotions; even “affective computing” focuses on recognition/simulation rather than genuine feeling, and anthropomorphism makes empathy seem present when it isn’t.

Myth 5: AI tools are ecologically and socially unproblematic.

Because many AI tools can be used free of charge, it can seem as if they are offered at little cost and therefore have few ecological or social downsides. The authors state that “the complete opposite is accurate”: they point to hidden human labor in data labeling (often in low-wage regions), potential psychological stress for workers reviewing harmful content, and significant energy demands—plus broader social effects such as reduced use of open educational resources.

Regarding the use of open educational resources, David Wiley offers an interesting counterpoint. He reminds the OER community that you should fall in love with your problem and not your solution. He states ‘there’s something very powerful about living in a time when we can ask for resources on the topics we need for the students we need it for’. His most rent work focuses on creating and sharing Open Educational Language Models (OELMs) to address some of the concerns towards generative AI put forth by Bozkurt el at. 2024.

Myth 6: AI tools act in accordance with the law.

People may assume that common uses—researching private information, uploading texts or images, or asking questions about proprietary materials—are basically fine and will stay “inside” the tool. The paper highlights concrete legal and institutional risks around copyright and data protection. It states that according to Austrian copyright law uploading a single textbook page to an AI tool for the purpose of generating a classroom quiz may be illegal. The authors challenge the assumption that interactions always remain private, and note uncertainty about how/where data are used.

Myth 7: AI tools render knowledge and competence acquisition obsolete.

Because AI-generated results can be impressive—especially when users aren’t deeply familiar with a topic—it’s easy to feel AI can do many tasks instead of you, making learning and expertise seem less important. The authors argue that many professions will still require understanding AI’s functioning and typical errors to correct and use outputs appropriately, and that detecting errors/bias and counteracting undesirable developments often demands detailed knowledge, conceptual understanding, and moral judgment.

As Rick West warns: “we shouldn’t assume it’s always going to be beneficial. At times, our field can be too forgiving of technology’s faults. We get caught up in the allure of a shiny new technology without considering its negative aspects. We need to be honest with ourselves about the challenges and negatives. We need to question when we should be using these tools with younger minds.”

Similarly, Alec Couros points out: “Our students are growing up in a media environment of unprecedented synthetic saturation… The deepfake is no longer an edge case; it’s becoming the default texture of the information landscape. In this environment, critical media literacy isn’t just a nice academic skill. It’s a survival capacity. The student who has never struggled to find their own voice will have no ear for the synthetic… no instinct for detecting the fabricated.”

Your Thoughts?

The report tackles an important question: How do users conceptualize generative AI and does this create unwarranted trust? Punya Mishra (2026) analyzed a publicly available dataset from a nationally representative August 2025 survey (2,301 U.S. adults) by Searchlight Institute and Tavern Research to see what people think AI chatbots are doing “under the hood.” He finds that the public mostly understands the surface function of chatbots (86% correctly say they write/answer with text), but understanding collapses when asked about learning and response generation: only 39% correctly identify “learning from huge amounts of text,” while many believe either explicit programmer rules (33%) or humans typing answers (23%), with accuracy higher among college graduates, frequent users, and younger respondents (Gen Z best; older adults most likely to choose the “rules” model). The most consequential misconception shows up when people explain what happens when you ask a question: only 28% correctly identify next-word prediction based on learned patterns, while 45% think the chatbot is looking up exact answers in a database (and even regular users often believe this).

The position paper by Schön et al. aims to foster critical AI literacy by exposing the gap between how AI appears to function and how it actually operates. You may not agree with every point, but starting the discussion is crucial for responsible implementation in schools and universities. Leave a comment on what myths you have encountered in your students or coworkers, what concerns you share, where you disagree, and what additional downsides you see.

Learn more:

Report:

Schön, S., Brünner, B., Ebner, M., Diesenreither, S., Hanfstingl, B., & Krammer, G. (2026). Seven Myths of AI Use (Report). Graz University of Technology.

German Language Version:

Schön, S., Brünner, B., Ebner, M., Diesenreither, S., Hanfstingl, B., & Krammer, G. (2026). Sieben Mythen der KI-Nutzung (Report). Graz University of Technology.